Sunday, July 6, 2008

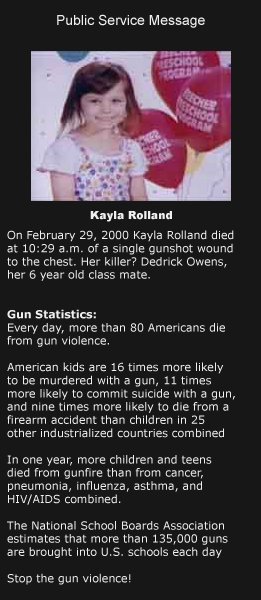

Flames raise in front of a police building in Weng'an China on Saturday, June 28, during a protest over officials' reaction to a student's death.

Aftershocks from the huge protests that took place on June 28 in the remote town of Weng'an continue to reverberate, with news breaking Friday that both the local Communist Party commissar Luo Liaping and the chief of police, Shen Guirong have been dismissed for what official media reports described as "severe malfeasance." Such speedy and decisive action by Beijing is, to put it mildly, unusual. That reflects both the gravity of the riot, which involved up to 30,000 people, and a desire by the central authorities — currently consumed by the build up to the Olympics — to stop the protests from continuing. But there are other signs that the incident is more than a mere pre-Olympics anomaly and may be part of a new, more open approach by Beijing to outbursts of long-simmering rage.

On June 28, tens of thousands took to the streets of Weng'an, a rural town in remote Guizhou Province, to protest what they believed was a cover up by the local authorities of the alleged rape and murder of a 15 year-old schoolgirl, Li Shufei. The protesters torched upwards of 20 cars and set fire to both the local police station and the Communist Party headquarters. Even before the dismissals of top local officials, it was clear this incident was going to be treated differently. On July 3 the provincial governor, Shi Zongyuan, made an unusually blunt statement condemning the conduct of the local police. His words drew a surprisingly revealing picture of the reasons behind the incident. Although on the surface it was sparked by the controversy over the schoolgirl's death, the governor said, the real reasons for the scale and violence of the protests were the suppressed anger at the behavior of local officials. He cited the demeanor of local government officers in denying residents the economic benefits of mining (read, large scale corruption) and the use of force during the resettlement of migrants and forced demolitions to make way for development projects

The governor's comments were particularly unexpected given that such protests in a remote county like Weng'an would normally be relatively unremarkable. Even the central government admits that such "mass event," as it terms them, are common, noting that some 87,000 occurred in 2006 (though the definition of what exactly constitutes a mass incident is vague).

Coverage of the "mass event" by the state media was also surprising. Normally such stories are ignored or simply dismissed by noting, for example, that a dozen farmers were arrested for disturbing social order. But this was different. Xinhua, China's official news agency, responded quickly and produced unusually long investigative stories. China's two largest websites, Sina and Sohu, published a headline about the incident on their front pages and updated their stories every few hours. And the local Guizhou television network broadcast live coverage up to 24 hours after the incident occurred, even showing the Weng'an police headquarters in flames, usually a strong taboo in China.

The Weng'an incident and its seemingly more open coverage are signs of the greater latitude enjoyed by the state media in the wake of the May 12 Sichuan earthquake. While the more lenient earthquake coverage appeared to be a spontaneous decision taken by Beijing, some observers believe that the extensive coverage of Weng'an could be a direct result of a policy change in Beijing signaled by a speech given in late June by Chinese President Hu Jintao. During a visit to offices of the Party mouthpiece, the People's Daily, Hu stressed that the media needed to concentrate on molding the public's perceptions of news events and presenting their reports in a more attractive and innovative way. To close observers of the party, this appeared to signal a new policy direction. "It seems the party will allow the Chinese media to report more transparently," says Russell Moses, a Beijing based scholar, "though of course they still dictate the lines of authority."

If the traditional media's coverage of Weng'an was allowed to be more "open," however, the online censors didn't seem to have got the same memo. The struggle between the ever inventive Chinese users of the Web and the Great Firewall, the Chinese internet censorship system, could be seen in a sort of online game of whack-a-mole, as posts, pictures and video of the rioting and its causes were deleted within hours, or even minutes, of being posted. But the locals have continued to create new ways to avoid being blocked. Instead of posting on social discussion forums, where such topics are usually raised, netizens wrote about the incident on video game bulletin boards and other unrelated sites. They also used jocular code words for the incident ("bonfire party") and deployed special software that reversed sentence order so that lines ran from right to left and horizontally instead of vertically. Xiao Qiang, a Berkeley-based Chinese media expert thinks the government censors lost this round. "In this particular case, netizens' anger was just too strong to be suppressed," he says.

Labels: China

0 comments:

Post a Comment